How to Interpret Scientific Claims (and Discrimination in Research)

By Claire Sehinson, Head of Research at The Optimum Health Clinic

As practitioners, we are trusted by our clients to practise safely and in an evidence-informed way. This means that we have to ask certain questions when reading the research to ensure the interventions are safe to use, relevant to our client’s demographic and efficacious in the condition we are recommending this for. We need to analyse all aspects of the study and read them with a critical eye to minimise the risk of mis-information or over-interpretation of results.

Journalists may have a reasonable understanding about the health conditions they report on and conclusions that the researchers have drawn from their data, but within the scope of a short news article, reporting complex findings with many possible interpretations isn’t always possible. Historically views have not always been balanced, nuanced enough for complex health conditions or generalisable to everyone.

As practitioners representing vulnerable people with poorly understood and complex health conditions, we get lots of questions about promising new treatments and alternative therapies that say they have been “backed by research” from people desperately hoping that this is their magic bullet and answer to all their problems.

Past experience has shown us that even large-scale heavily funded studies can get it wrong. Particularly where trials have been poorly designed or there is a lack of understanding about the root cause of the illness. The sheer size of some studies means they tend to dominate clinical policy resulting in the mis-treatment and stigmatisation of thousands of people. This includes:

Graded exercise therapy in CFS/ME from the results of PACE trial which has now been revoked

Measures and metrics: The BMI (body mass index) is no longer in use and fails to account for variables like ethnicity, gender, muscle mass and type of fat.

Nutrition advice that eggs are bad for your cholesterol levels is now known to be a myth, as well as low calorie diets for long-term weight management.

Top tips when reading scientific claims related to health

Correlation is not causation

Correlation is where there is a statistical relationship between two things and they fluctuate together. This does not however imply that one is causing the other. In health research a common mistake is to assume that because one factor is correlated with another, it is causing it.

For example, the study below found a correlation between chocolate consumption and Nobel prize winners, where the higher the amount of chocolate consumed in a country, the more Nobel prize winners there were.

It would be wrong to interpret this science to mean “eating more chocolate causes more people to win Nobel Prizes” and also there is no implication about the direction of causality either, “Winning Nobel Prizes results in more chocolate being eaten”.

There could be an underlying causal relationship between these two variables, but a different study would have to be conducted to find this out. The correlation could also be completely down to chance.

Spurious correlationsis an entertaining website that makes us think about statistics and the number of ways they can be presented and mis-interpreted, for example:

Retrospective studies analyse historical data (such as medical records) to look for relationships between exposures and outcomes. This study is widely used in epidemiology to understand what types of disease a population might be at risk of for example: the risk of lung cancer in smokers, or rates of anxiety disorders in teenagers following the COVID pandemic. The data has usually been collected for other purposes (than the study) and there are no ‘interventions’ only observations of past events. Data can be poor quality or inaccurate, lack context or important information may not have been recorded at all. We need to remember that any associations drawn from these studies are correlations and not causation.

2. Research is Inherently Biassed

Bias refers to anything that can influence or distort the results of a study, leading to conclusions that are not reflective of the true situation.

There are many types of bias in research, here are common types to be aware of:

Publication bias.

It is known in academia that studies with positive findings are more likely to be submitted and published by journals than null or negative findings - and this is especially true for psychiatry and psychology. However negative findings are just as important to science as positive findings.

The lack of “statistical significance” (null finding) is not concrete proof there wasn’t an underlying effect, it means it was not detected on this occasion which could be due to a number of things such as the sample size (number of participants) being too small to detect a change (low statistical power).

Larger studies that have more funding carry more “weight” and “power” and this means they are more likely to be influential in developing medical guidelines and clinical policies.

Meta-analyses (considered the gold-standard in research) use statistics to combine the knowledge from multiple studies, aiming to come to a general consensus. However they are only as strong as the studies included, if they are made up of poor quality studies the meta-analysis will produce misleading results. This is known as GIGO “garbage-in-garbage-out”. Similarly if they mainly contain positive-findings because of less null-finding publications, they won’t be representative of the true situation.

Selection bias

is where the group of people included in the study is not representative of the larger population at whole. For example, the majority of research in genetics and genomics has been done on european descendants and the white western populations so we have to be careful when applying these findings to a different population to the one that was studied.

Funding bias

occurs when the outcomes of the study are consciously or unconsciously influenced by the organisation providing the funding. An example highlighted in this Vox article found that Mars has funded over 100 studies on the health benefits of chocolate and cocoa with overwhelmingly positive results undoubtedly to shift the public perception of their chocolate products.

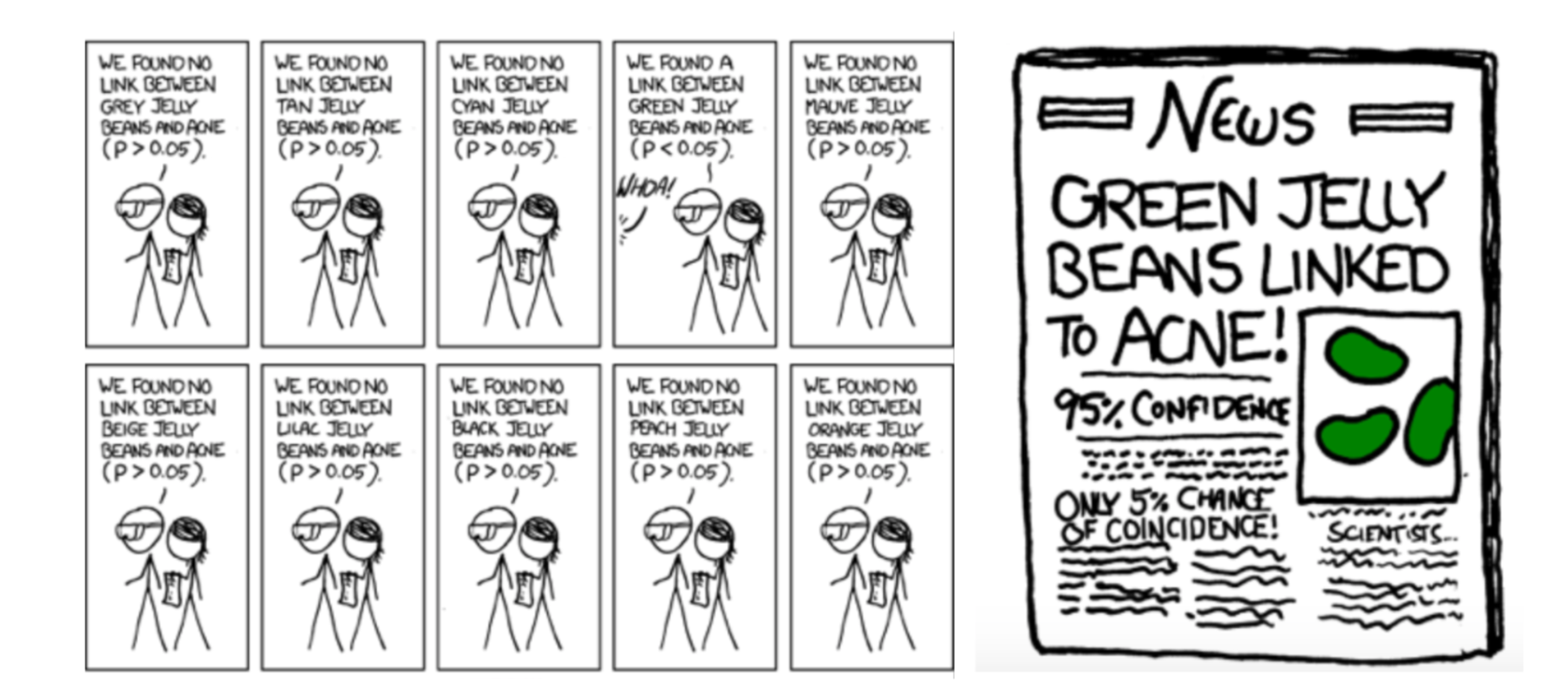

Data dredging / analysis bias

these are all ways the data can be ‘manipulated’ or ‘cherry picked’ in order to produce a statistically significant finding, when actually the results may be down to chance.

An example is the PACE trial on CFS/ME patients which dominated clinical policy for a long time due to its size and funding before it was realised that graded exercise therapy (GET) was harming a lot of ME/CFS patients. GET is now removed from guidelines.

This article is one of many documenting the statistical and design flaws in the most expensive ME/CFS trial to date. This series of videos on the PACE trial created by a mathematics teacher explains the design flaws and the data-dredging that caused so many researchers, healthcare professionals and patients to appeal for its reanalysis.

3. In Vivo or In Vitro?

When examining health claims drawn from a study, we want to understand the “how and in who?” to assess if this is relevant for us.

A day in the life: navigating autism research as an autistic researcher

4. Statistics:

Everyone’s least favourite section of a paper, but it is important to understand what these numbers are telling us so we don’t over or underestimate the results:

5. Discrimination and exclusion in research:

Discrimination and exclusion are significant issues in research which results in unequal access to healthcare for marginalised populations. This mistreatment contributes to poorer health outcomes and harm to the individual/marginalised communities and distrust of the healthcare system by these populations.

This type of bias is one of the biggest ethical issues for future research, and in particular, the use of AI in retrospectively analysing studies to generate more data (if you remember the Garbage-in-Garbage-Out principle).

Gender:

women and other gender minorities have been historically excluded and under-represented at every stage of clinical research from in vitro (male cells used over female cells), animal studies (even male rats over female rats) to clinical trials. This knowledge gap perpetuates outdated stereotypes about women and other gender minorities. Physical symptoms can are often dismissed as psychological, leading to misdiagnosis or delayed diagnoses of significant health conditions such as heart disease. There is a paucity of research, available treatments or even much interest in fields that disproportionately affect women include autoimmunity, pain, migraines and CFS/ME.

LGBTQIA+ individuals

have alarmingly high rates of mental health issues and significant health inequalities as well as higher rates of chronic illness, substance misuse and eating disorders. There is a lack of specific training and education for healthcare providers and this results in LGBTQIA+ populations not able to access appropriate care (or services such as IVF) and gender-affirming therapies. There is also a lack of clinical research in LGBTQIA+ populations with many of the existing historical studies being riddled with harmful stereotypes and misinformation (based on what society deems as normal i.e. the male/female binary for gender expression). This lack of understanding about the LGBTQIA community leads to flawed study designs, biassed data and the creation of harmful policies, practices and stigma.

Ethnicity:

people of colour are under-represented in medical research to the degree that clinical training and medical textbooks do not adequately equip clinicians with the skills to assess people of colour in an accurate or culturally appropriate way. Without training to visually identify signs and symptoms on black and brown skin (that we take for granted on white skin), such as a bulls-eye rash (indicating Lyme disease), cyanosis (the blueish grey tinge to the skin suggesting anaemia), jaundice (the yellowing of the skin that could indicate liver disease), erythema (redness and swelling due to inflammation) serious and life threatening conditions get picked up much later than in a person with white skin which is one of the contributors to the huge health disparities in people of colour.

A recent study shows patients from a Black, Asian and Ethnic Minority background were 4 times more likely to die or have serious health complications from COVID19/SarsCoV2, which highlights the need for education and research in these populations. Mind The Gap is a free textbook created by BPOC physicians to help to bridge the knowledge gap and save lives.

In addition, many of the routine metrics we use assess health risks such as the BMI (Body Mass Index) stem from non-scientific and racist origins. The BMI was created by a mathematician in the 1800s calculating the average height and weight ratios in white European men and had nothing to do with health. Furthermore it didn’t account for different body sizes, body types or body fat distributions in diverse ethnicities or genders. Yet the BMI has been a barrier to people accessing life saving surgeries, diagnostic assessments, medications and gatekeeping IVF.

Studies have repeatedly demonstrated the BMI is a very poor indicator of health the most obvious argument being athletes or those who have a higher muscle mass/weight are often classified as ‘clinically obese’ by this metric which has no relationship with their actual health risk. See recommended reading list below if this topic is of interest.

Disability:

People with disabilities are largely absent from health research including public health and epidemiological research. Some of it is due to research design such as exclusion criteria - this is where people would be excluded from a study, say on cardiovascular disease because they have another medical condition (I.e. diabetes) as this could muddle (confound) their nice neat datasets. Other people would be excluded based on the inability to physically travel to research centres or take part in interviews due to verbal or written communication difficulties.

Yet people with disabilities suffer chronic health and mental illness at a higher rate either directly related to, secondary to or co-occurring with (not necessarily related to) their disability.

Similarly people with ‘invisible disabilities’ such as Ehlers Danlos Syndrome, Chronic fatigue syndrome or ones that can sometimes be masked/hidden (including neurodivergence) may not receive appropriate care, accommodations or have access to financial support (even though disabilities are a protected group by law) because they “do not look or behave in a certain way” according to their “disability criteria” a stereotype that disability as a certain look or behaviour.

People with these disabilities can feel shame or experience stigma when attempting to access supports as highlighted in this article. The problem with this is when people without lived experiences make judgements about people based on poor understanding, this leads to devastating outcomes for the disabled person’s mental and physical wellbeing.

An example of this is a study conducted on the illness intrusiveness, disability and symptoms in patients with CFS/ME compared to other severe illnesses such as lung cancer, Multiple sclerosis and rheumatoid arthritis, CFS/ME was found to be the most intrusive on daily life. Yet many people with CFS are unable to prove how disabled they are with financial support withdrawn.

Social determinants and socioeconomic status:

The world health organisation states that social determinant of health (SDH) - all of the non-medical factors such as education, poverty, access to safe and affordable housing, access to nutritious food, social inclusion and discrimination - have more influence over health and our lifespan than lifestyle, psychological or biological factors, with numerous studies estimating that SDH accounts for 30-55% of health outcomes. This is broken down in Michael Marmot’s book The Health Gap and The Marmot report (Institute of Health Equity).

Health Equals data in the UK found that one of the biggest predictors of a shortened lifespan was your postcode (zip code), with a difference of an 18 years between living in an area of poverty or affluence. Whilst exciting research in personalised and functional medicine, nutrition and lifestyle interventions and psychological therapies emerge, this will undoubtedly exclude the poorest and most vulnerable people in society who will be unable to access this support.

Conclusion

Scientific research is a fantastic tool to understand the world and ourselves through observation, experimentation and data. However in this article we have covered just a fraction of the limitations and ethical considerations with this process. Many complex systems (including human beings) cannot be captured by current scientific measurements or distilled down to a few simple numbers (known as reductionist science). History is littered with unethical experiments and harm done to vulnerable groups of people, including black Americans from colonial times to the present day and Autistic people in Nazi Germany - all in the name of science.

The misinterpretation of a study or poor/lazy journalism in news and media articles may add to the misinformation, stigmatisation and harm done to vulnerable people who are desperate to feel better.

As practitioners we constantly evaluate the research and combine these findings with our client’s lived experiences to provide safe and evidence-informed care.

Further reading list

Discrimination and Inequality Not an exhaustive list

Dalia Kinsey - Decolonizing wellness

How the use of the BMI Fetishizes White Embodiment

Annabel Sowemimo - Divided: Racism, medicine and why we need to decolonise healthcare

DE Hoffman - The Girl Who Cried Pain(Bias Against Women in the Treatment of Pain)

Transactional (trans and healthcare inequality)

Gender specialist - Rebecca Minor

More academic: Conducting Research on the Health Status of LGBT populations

Statistics