Part 2: Interoception, Alexithymia and Aphantasia

Alexithymia is the one thing I wish I had known about as a Neurodivergent person trying my best to engage with the medical system and therapies since my late teens, and also as a clinician working with neurodivergent clients. Alexithymia is an emotional processing difficulty that is a byproduct of interoception differences and exists on a spectrum from mild-to-severe.

It affects 10% of the general population but it is estimated to affect 40-65% of autistic people and 41.5% of ADHDers (where this has a relationship with impulsivity).

The literal meaning of Alexithymia is “without words for emotion”. Very importantly, it doesn’t mean that the person isn’t feeling emotions, you can be feeling something very strongly, just not able to identify or verbalise them.

Alexithymia can be primary (you are born with it) or secondary, often acquired after PTSD or a traumatic brain injury (such as stroke). A large meta-analysis of over 36,000 participants revealed that alexithymia has an alarming correlation with various forms of childhood trauma. Primarily emotional abuse, physical abuse and emotional neglect being the strongest predictors of Alexithymia in adults and this puts them at higher risk of developing a wide range of mental health disorders (known as a ‘transdiagnostic factor’).

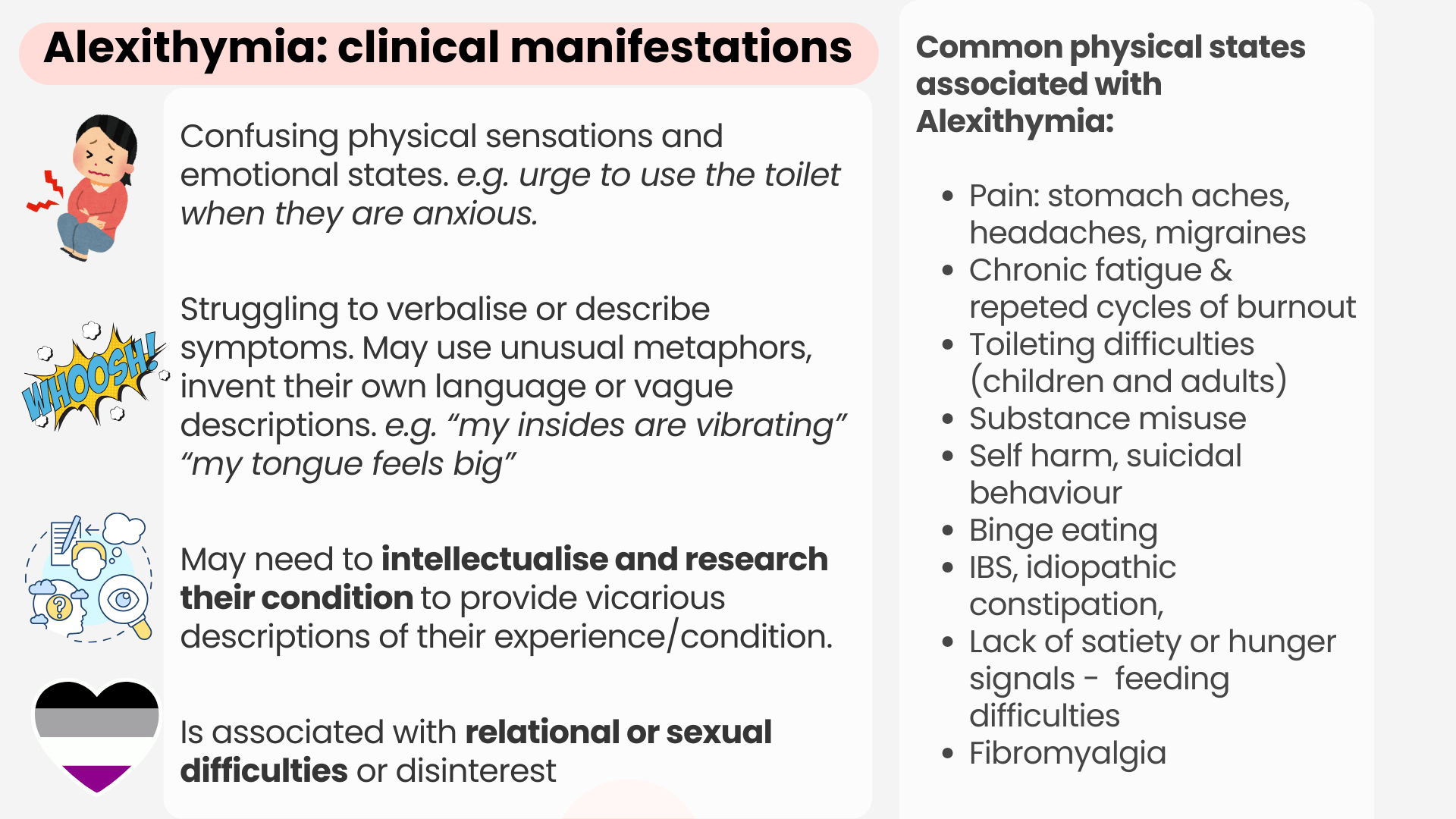

Alexithymia is defined by:

Difficulties identifying, expressing or describing emotions or feelings (not to be confused with the inability to feel). We can often be experiencing “vague dread” or “impending doom” but not be able to identify the source.

Difficulties telling the difference between emotional states and physiological sensations. So we may confuse body sensations with emotions (such as the urge to go to the toilet when you’re anxious, or feeling like you’re hungry when you are actually bored.

We can also struggle with interpreting someone else’s facial expressions and body language but highly sensitive to 'emotional tone’ that feels incongruous with how the person appears to be emoting or what they are saying. This inability to match up feelings and reality creates a lot of uncertainty and anxiety.

Alexithymics tend to be focused on and more connected to the external world than our inner experiences.

People with alexithymia often are unable to pick up on subtle shifts in emotions or register sensations until they are very intense. For example, not registering the need for food until you are absolutely famished and physically shaking.

By the time you’re at that level of discomfort it’s much harder to regulate yourself, so from an outsiders point of view you can be appearing to have more dramatic mood swings, shutdowns/meltdowns or go into a vagal-freeze state. This can be linked the uses of substance misuse, food addictions or even self-harm as an attempt to alter our state.

Alexithymia affects our communication and there are often difficulties describing pain, symptoms, needs or our emotional state to practitioners or therapists. Filling out health questionnaires (particularly those on a linear scale) can feel near impossible!

As described in part 1, what underlies alexithymia are interoception differences in they way we perceive, assign meaning to and interpret sensory information and this underprisingly leads to a large array of mental health consequences.

Aphantasia - “mind blindness”

…Picture a ball on a table..

…what colour was the ball? what type? (a tennis ball? a football?) or was it just a faint circular outline?

…what was the table made out of? was the table in a specific room in your house or floating in space?….

I am a highly visual person, so I could picture with a very high degree of detail what that ball looked like on a table, the table was also in my parent’s kitchen where I grew up which immediately initiated a chain of associated memories… But not everyone will be able to do this. People sit somewhere on the spectrum of ability to conjure up visual imagery on demand. Some people might have only been able to generate an outline of a ball on a table floating in space. Others may not be able to do it at all.

Aphantasia is the difficulty or complete inability to voluntarily visualise or create mental pictures, and this is estimated to affect 2-4% of the population but it is very likely that the figure is much higher because often people don’t realise their mind works in a different way. My friend with Aphantasia always thought “picturing yourself walking on a beach” often used in guided meditations was a metaphor and no one could actually do this!

This highlights the point that people with Aphantasia are likely to struggle with therapy modalities that are heavily reliant on visualisation (e.g. hypnotherapy, meditation, EMDR and NLP) and need to be adapted.

Although more research needs to be conducted, it is thought that Autistic people and ADHDers may have higher incidences of Aphantasia. Aphantasia can be congenital (born with it) or acquired (secondary to depression or brain injury, and some people suggest trauma).

Aphantasia will affect how memories are encoded, such as the amount of detail in long-term memory (for example difficulties remembering what someone from their childhood looked like), as well the capacity to hold things in short-term memory (where room did I last see my phone?!).

Aphants (people with aphantasia) will often have more pronounced or be reliant on other types of memory such as auditory memory, sensory/feelings or body-based memories and verbal or autobiographical memory. They often describe navigating the world through how they feel and their emotions, which could be one reason there appears to be a higher co-occurrence with ADHD. It could also impacts on how trauma and PTSD are experienced (i.e. body-based or sensory flashbacks rather than visual).

This video describes Aphantasia in a way that has resonated with all of my Aphantasic patients and friends and includes an interesting discussion on moving on after relationship breakups and possible protection against PTSD. Anecdotally friends have shared that the bereavement period may have been shorter for them compared to siblings without Aphantasia and the inability to conjure up visual images could have contributed to this.

The VVIQ is a scoring scale for vividness of your abilty to visualise.

In conclusion

As neurodivergent people with perceptual and interoceptive differences, we are also conditioned to believe we should think and feel in a neurotypical way which are often not comparable with our true experience. This can make us feel incompetent, misunderstood and hopeless in the doctors office and in therapy sessions which unsurprisingly leads to feelings of shame and the inability to convey our needs, therefore much higher rates of a range of mental health conditions.